thebengalstory.com - devdanchaudhuri : If the Anglophone Indians are derided as ‘Macaulay’s children’, then the Hindi speaking Indians can also be called ‘Gilchrist’s children’.

thebengalstory.com - devdanchaudhuri : If the Anglophone Indians are derided as ‘Macaulay’s children’, then the Hindi speaking Indians can also be called ‘Gilchrist’s children’.My late maternal grandmother – who had studied philosophy and biology in the 1940s Calcutta – had told me once during my boyhood, that Calcutta was the birthplace of the modern Hindi language: it was ‘invented’ by the British in Fort William, Calcutta.

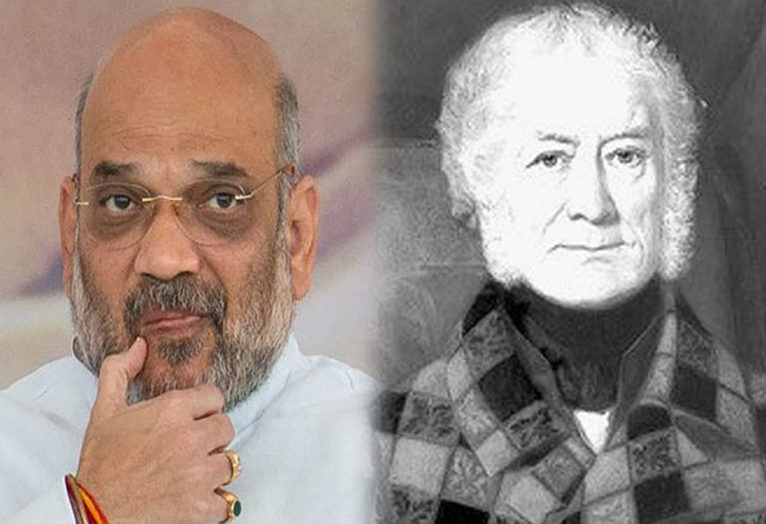

I remembered my grandmother’s words when I read the news reports about the recently concluded ‘Hindi Divas’ day when the Union Home Minister Amit Shah pitched for Hindi as the national language of India.

This prompted me to consider and figure out why my maternal grandmother said what she did. I wanted to know about the ‘suppressed truths’ and understand the ‘secret history’ of Hindi.

Now I wish to share with you what I found; and have to begin by recalling few essential facts about the languages of India.

Linguistic Diversity of India

Papua New Guinea – with a population of just over seven million – has world’s highest number of languages: 852 (840 are spoken and 12 are extinct). It tops the Linguistic Diversity Index (Source: UNESCO 2009) with 0.990. India comes at #9 with a score of 0.930.

But if we measure linguistic diversity by total population, India with 1.3 billion people (#2 by population) is much ahead of the rest, including China (1), United States of America (3), Indonesia (4) and Brazil (5). And hence, one can say, India is the ‘most populated linguistic diverse country in the world’.

Census of India of 2001 said that India has 122 major languages and 1599 other languages. It recorded 30 languages which were spoken by more than a million native speakers and 122 which were spoken by more than 10,000 people.

There are 22 scheduled languages of India – Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithali, Malayalam, Marathi, Meitei (Manipuri), Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telegu and Urdu – and two official languages of the Union Government: Hindi and English.

In addition to the above, the Government of India has awarded the distinction of classical language to 6 languages which have a ‘rich heritage and independent nature’: Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu.

Tamil is also one of the oldest living languages in the world and this Dravidian language predates even Sanskrit (a part of the Indo-Aryan family of Indic languages).

Contrary to the perceptions formed by boisterous disinformation campaigns, Hindi is not the national language of India. India has no national language.

As per the 2011 census, only 26.6% of the Indians identify Hindi as their mother tongue.

Hindi Language

Modern Hindi – one of the youngest Indian languages – is based on the Khariboli dialect (vernacular of Delhi and the surrounding region) and its literary tradition evolved towards the end of the 18th century.

Khariboli itself had evolved to replace earlier dialects such as Awadhi – the sweet-sounding language of the commoners in which Tulsidas’ Ramcharitamanas was composed in the early 17th century. The Awadhi bhakti poem popularized Lord Rama all over North India; that in turn is influencing the politics of modern India.

I have recounted the fascinating story of How did Lord Rama become a Hindu god? in an essay published in 2018.

Hindi evolved at a time, when Urdu – another form of Hindustani since the 1800s – underwent significant Persian influence and acquired linguistic prestige.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, under The East India Company, Hindustani was developed into separate Hindustani standardization: Hindi and Urdu.

This was also probably done under the cunning imperial ‘Divide and Rule’ policy to linguistically segregate religious communities – namely the Hindus and the Muslims – and build schisms, weaken the collective and incite demagoguery which will last through generations, and even centuries.

But this ‘linguistic division’ wouldn’t have been possible without one particular person who is virtually unknown in our ‘common collective memory’ of Indian history: the unsung father of modern Hindustani languages, John Gilchrist.

John Gilchrist – the Father of Modern Hindustani Languages

John Borthwick Gilchrist (1759-1841) was a temperamental Scottish trained-surgeon and self-trained linguist – a failed banker in his native city Edinburgh – who spent his early career in India where he studied Hindustani languages.

Chambers’ Biographical Dictionary describes him in his advanced years as “his bushy head and whiskers were as white as the Himalayan snow, and in such contrast to the active expressive face which beamed from the centre of the mass, that he was likened to a royal Bengal tiger – a resemblance of which he was even proud.”

In 1782, Gilchrist was apprenticed as a surgeon’s mate in the Royal Navy and travelled to Bombay, India. There, he joined the East India Company‘s Medical Service and was appointed assistant surgeon in 1784.

During Gilchrist’s travels in India, he developed an interest to study Hindustani languages. In 1785 he requested a year’s leave from duty to continue these studies. This leave was eventually granted in 1787 and Gilchrist never returned to the Medical Service.

His first publication was A Dictionary: English and Hindoostanee, Calcutta: Stuart and Cooper, 1787–90. He popularized Hindustani as the language of British administration and suggested to the Governor-General, the Marquess of Wellesley, and the East India Company, to set up a training institution in Calcutta. This started as the Oriental Seminary or Gilchrist ka madrasa, but was enlarged within a year to become Fort William College in 1800 within the premises of Fort William in Calcutta. Gilchrist served as the first principal of the college until 1804, and continued to publish a number of books including The Hindee-Roman Orthoepigraphical Ultimatum, or a systematic descriptive view of the Oriental and Occidental visible sounds of fixed and practical principles for the Language of the East, Calcutta, 1804.

Gilchrist inducted Indian writers and scholars into the college, and offered them financial incentive to write in Hindi. The contributions by the Indian writers and scholars enabled rapid strides in Hindi language and literature in a short period of time. Gilchrist’s initiative produced the popular Premsagar (Ocean of Love) by Lallulal (1763-1825). Subsequently, a Hindi translation of the Bible appeared in 1818 and Udant Martand, the first Hindi newspaper, was published in 1826 in Calcutta.

Gilchrist wrote ‘bifurcation of Khariboli into two forms – the Hindustani language with Khariboli as the root resulted in two languages (Hindi and Urdu), each with its own character and script.’

In other words, what was Hindustani language was segregated into Hindi and Urdu (written in the Devanagari and Persian scripts), codified and formalised.

Santosh Kumar Khare on the origin of Hindi in Truth about Language in India wrote in his essay: ‘the notion of Hindi and Urdu as two distinct languages crystallized at Fort William College in the first half of the 19th century.’ He added: “their linguistic and literary repertoires were built up accordingly, Urdu borrowing from Persian/Arabic and Hindi from Sanskrit.’

In the words of K.B. Jindal, author of A History of Hindi Literature: ‘Hindi as we know it today is the product of the nineteenth century.’

Contemporary Dutch historian Thomas De Bruijin says that Fort William College in Calcutta was ‘more or less the birthplace of modern Hindi.’

George Abraham Grierson, noted Irish linguist of the late 19th and early 20th century, said that the standard or pure Hindi which contemporary Indians use is ‘an artificial dialect the mother tongue of no native-born Indian, a newly invented speech, that wonderful hybrid known to Europeans as Hindi and invented by them.’

Hence, my late maternal grandmother was right: the birthplace of modern Hindi is Calcutta. And it was in Fort William that this invention took place under the tireless efforts of John Gilchrist.

If the Anglophone Indians are derided as ‘Macaulay’s children’, then the Hindi speaking Indians can also be called ‘Gilchrist’s children’.

The Conclusion

In our ‘civilisational state’ of modern India – whose history goes back to 8000 years or more – a language that is just over 200 years old and a construct of our colonial imperial masters – that too by an employee of a rapacious private corporation, The East India Company – cannot possibly be considered as the national language of India.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s statements on the Hindi Divas day are indicative of the broader Hindutva agenda and the political attempt to impose Sanskrit as the ‘mother language’ and Hindi as the ‘national language’.

But Sanskrit isn’t the mother language of India. No single language can be called as the ‘mother language’ of our ancient land that contains such linguistic diversity that has emerged from several language families: Indo-Aryan or Indic, Dravidian, Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Tai-Kadai and Great Andamanese.

Neither Hindi – as pointed above – can be imposed as the national language of India. India needs no single national language; diversity is the fundamental national characteristic of India, and it should remain that way.

We – the Indians who don’t come from the Hindi-Hindustani cow belt – clearly understand that an organised ‘socio-cultural engineering mission’ is going on in India that wishes to ‘colonise’ – euphemistically ‘unify’ – all plural Hindu communities under the flag of singular ‘Hindutva’.

The imposition of Hindi language upon all Hindus who don’t speak Hindi is part of the larger political mission towards the establishment of ‘Hindutva Rashtra’ masquerading as ‘Hindu Rashtra’.

Article 29 of the India Constitution ensures us equality for all citizens of India as far as conservation of their language is concerned, their culture is concerned and their script is concerned.

Imposition of any single language upon the rest is constitutionally invalid, and the effort to do so – in midst of such linguistic, ethnic and cultural diversity of modern India – is likely to boomerang and cause more regional stresses, disharmony, disunity and disaffection.

India doesn’t require the ‘unity’ of ‘one language, one nation’. India needs to assert its own sovereign and unique ‘civilisational spirit’ of ‘Unity in Diversity’.

The Mother of All Ironies

In 2017 I published an essay to write about ‘How Hindus Became Hindu and Why Hindutva is not Hinduism’.

Now I also wish to point out – what I call – the mother of all ironies.

RSS-BJP-VHP or the Sangh Parivar’s Hindutva ideology is based upon four key words: Hindi, Hindu, Hinduism and Hindustan.

The Sangh ideology considers Muslims and Christians as phirang invaders into India. But it was the Persians who coined Hindu and Hindustan; and it was The East India Company and the British Empire which developed Hindi language and added ‘ism’ to Hindu.

Hence, the entire ‘identity, world view and nationalist’ politics of the Sangh Parivar is based upon what the ‘Muslims and the Christians’ gifted to us!

There can be no greater irony than this. This is the mother of all ironies; the height of all heights.

[The views expressed belong solely to the author, and may not reflect the opinions of the editorial team]

Write to us at letters@thebengalstory.com

கருத்துகள் இல்லை:

கருத்துரையிடுக